It was a scene ripped from a John le Carré novel.

According to firsthand accounts and court documents, a man is told to go to the front desk of the Four Seasons Hotel in downtown Manhattan and say the phrase “banana peel.” The concierge then hands him an envelope with orders to circle the block twice before receiving further instructions. He returns, is shuffled into a secret elevator — one that isn’t even used for celebrities, only visiting dignitaries deemed assassination risks — and brought to the penthouse suite.

After 15 minutes, Sun Lijun enters the room and lights a cigarette. The man recognizes Sun, not merely because he is the third-highest-ranking official in China. In fact, they had met during a trip the man took to Hong Kong in which Chinese Communist Party officials confiscated his passport, blindfolded him and drove him into mainland China. Sun doesn’t greet the man sitting on a plush couch at the Four Seasons. Instead, the CCP bigwig pulls out an email from Attorney General Jeff Sessions regarding three American hostages being held in China. One is a pregnant woman. Sun asks the man what should be done about the woman. He suggests that in an act of good faith, she should be released. Sun makes a call, and after a few minutes, shows the man an itinerary — proof that the woman will be freed and flown back to the United States. A week later, at the tail end of 2018, the feds close in on the man as he walks into Lure, his favorite SoHo haunt.

But here’s the part that le Carré’s editors would have rejected as wildly implausible. The man is Pras Michél, founder of the legendary hip-hop band the Fugees. And his life is about to descend into chaos as he becomes the highest profile target in a labyrinthine criminal corruption case stemming from one of the world’s biggest financial scandals — the $4.5 billion looting of Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund known as 1MDB.

“I don’t know if subconsciously it was a bit exciting for me too,” Michél recalls in his first interview since being convicted in that case. “I like spy movies, but I never wanted to be a spy. I don’t think that’s sexy. But a part of it felt like that.”

If there was one red flag that something was off that night, Michél says it was the elevator. As a celebrity who has performed before crowds of 100,000, Michél was familiar with being whisked in and out of hotels by security. This was … different.

“I’m going to tell you what was weird to me: the fact that the Four Seasons has a private elevator. I never knew that. They have a private elevator for just certain people,” he says. “But my life leading up to that point felt surreal, so part of that night felt natural.”

Last April, a jury convicted Michél on 10 counts, including violating campaign finance laws during Barack Obama’s 2012 reelection bid and illegally lobbying the Donald Trump administration in 2017. The circus-like D.C. trial lasted three weeks and featured Leonardo DiCaprio testifying for the prosecution and everyone from Kim Kardashian to Martin Scorsese name-checked during testimony.

“Michél played a central role in a wide-ranging conspiracy to improperly influence top government officials, including the then-president [Trump] and the then-attorney general [Sessions],” said Department of Justice special agent in charge Harry Lidsky. Likewise, Luis Quesada, assistant director of the FBI’s Criminal Investigative Division, claimed that Michél “brazenly conspired to help a foreign national launder millions of dollars in illegitimate campaign contributions into the 2012 U.S. presidential election.”

In short, the government dubbed Michél a Chinese spy, and a jury agreed. He now faces 22 years in federal prison.

“Technically, I’m a foreign agent,” he says.

How a Yale-educated musical prodigy who made up one-third of a Grammy-winning group got caught up in this mess makes it one of the most riveting celebrity sagas in years. At the center of the tale is Jho Low, the wild-spending financier who burst onto the scene in 2013 by backing “The Wolf of Wall Street,” Scorsese and DiCaprio’s $100 million look at financial fraud and bacchanalian excess. As Low’s influence in Hollywood grew, scores of celebrities partied on his private jet, drank his Cristal and accepted his lavish gifts (DiCaprio landed a $3.2 million Picasso and a $9 million Basquiat), at least until his elaborate embezzlement scheme unraveled and he became a fugitive. For his part, Michél entered Low’s circle after the two were connected in 2006 via a party promoter who caters to the rich and shameless.

Low’s world extended beyond Hollywood to include political operatives — like Democrat Frank White Jr., a relation of Michelle Obama by marriage, and Republican fundraiser Elliott Broidy — who did his bidding. White has never been charged, while Trump later pardoned Broidy. Michél says he and Low were never friends, but he connected the deep-pocketed newcomer to other VIPs. He remains the only one in Low’s orbit to face real consequences.

“The government needed a prize. They needed a head, and he was the low-hanging fruit,” says Robert Meloni, a litigator on Michél’s team.

On an overcast September day in New York, Michél, now 52, takes me down the rabbit hole. We meet in his sparsely furnished 4,500-square-foot SoHo apartment with floor-to-ceiling views of lower Manhattan — a maroon couch, a baby grand piano and a shelf showcasing his Grammys are the only signs of occupancy. The walls are completely bare save for a giant TV. You might assume the government confiscated Michél’s furnishings. But you’d be wrong.

“I’m a minimalist,” he explains.

Wearing a gray Dolce & Gabbana T-shirt with “Love Is King” emblazoned on the front, jeans, pink socks and sandals, Michél exudes a post-yoga-class calm despite a looming sentencing date in January.

“I’m going to fight, and I’m going to appeal, but there’s a possibility that I’m going in while I’m fighting,” he says. “It’s just the reality.”

Michél was charged under the Foreign Agents Registration Act, a once rare maneuver. From 1967 to 2018, the feds only brought forward 12 criminal cases under FARA. But there has been a newfound zeal over the past six years, particularly against members of the Trump administration. Michél says the feds even threatened to use the Logan Act against him. Only two people have ever been indicted under the Logan Act. Adding to his woes, the government seized roughly $80 million from him. In the initial indictment, officials accused him and Low of illegally trying to “obtain foreign access to, and influence with, high-ranking United States government officials for financial benefit.”

“Every aspect of my life has been disrupted. I can’t bank anywhere, been kicked out of 13 banks,” Michél says.

Still, there are hints of wealth on display. A vintage Patek Philippe watch adorns one of Michél’s wrists, and Cartier and Tiffany bracelets hang on the other. Michél insists that he was never motivated by money. Instead, after the Fugees disbanded in 1997, he continued to land Grammy nominations as the artist behind the seminal “Ghetto Supastar (That Is What You Are),” but he also became a documentarian who traveled to dangerous locations to make gonzo films like “Skid Row” (embedding in L.A.’s homeless community) and “Sweet Micky for President” (which chronicled Michel Martelly’s bid for Haiti’s presidency amid civil unrest unleashed by the 2010 earthquake). He got comfortable being uncomfortable.

“I love being able to go stay at the penthouse in the Ritz-Carlton and then being in some fucking locked-up dungeon in Somalia eating rice with my hands,” he says. “When I was kidnapped [there], they were about to sell me to Al-Shabaab, the terrorist group. We were trying to do a documentary. I remember my director was freaking out. He was going crazy. He’s like, ‘Yo, you have a death wish on you, Pras. I should have never listened to you.’ I said, ‘Well, look at it like this. You shot some stuff. Maybe the footage would get back to the States. If we die, at least we got to tell a great story.’ He’s like, ‘What the fuck? What you mean a great story?’ And obviously State Department came and got us out.”

Shayan Asgharnia for Variety

Perhaps that’s why he was unfazed by Low’s cartoonish grandiosity and the strange asks he began to make. Low threw money around like a sultan, hosting Vegas birthday bashes and Cannes blowouts. But in 2012, as the feds closed in, Low struggled to keep his fraud operation from being exposed. The Malaysian financier tried to leverage his White House ties. He turned to Michél, an Obama fundraiser, and offered him $20 million for a photograph with the president. Michél obliged and kept most of the money. His thinking was rich people will spare no expense to meet famous people.

“I know people like [Low] who legitimately have money, and they’re wild,” he explains. “If they want something, they’re going to go through all means to get it because they have the resources to. People say, ‘People do crazy things,’ but they haven’t actually witnessed it. I’ve witnessed it.”

Case in point, the billionaire who lives on the top floor of his SoHo building.

“This guy wanted a statue. They literally shut down this whole block for a whole day, had to bring a crane, had to literally do a hole in the roof to bring the statue he wanted in, and then they redid the roof. He paid for it, obviously. But the roof is not his. It’s for the building. But he’s a billionaire, so it’s like … ,” he says with a shrug.

And Low’s spending kept him on the government’s radar. As his house of cards teetered, he tapped his political connections and turned to Michél again. With the turnover from Obama to Trump, Low hoped the new administration would go easy on him and unfreeze his assets. That’s where the Chinese government fit in. During the Hong Kong trip Michél took with Low, the CCP conveyed that it wanted the United States to extradite a fugitive named Guo Wengui. In exchange, it would release three U.S. prisoners, including the pregnant woman. The scheme faced obstacles, namely that Guo happened to be a Steve Bannon pal and a member at Donald Trump’s club, Mar-a-Lago.

By the time of the Four Seasons meeting, which Low orchestrated, Michél was already in the feds’ crosshairs. When the FBI began asking him questions, the rapper never requested a lawyer, believing that his actions were legal. After all, he was being advised by George Higginbotham, a senior congressional affairs specialist at the Department of Justice.

“The one person that I relied on, especially legally, didn’t give me the best advice,” Michél says. “That’s his job. I’m an artist. There’s a reason why you rely on your legal counsel. They’re the one that’s going to sit here and tell you, ‘Nah. OK, if you want to do this, do it this way so you don’t have any exposure.’ So if my representative is sanctioning what I’m doing and my representative coincidentally works for the DOJ, I am not going to sit here and think I’m wrong, right?” (Higginbotham did not respond to a request for comment.)

The prosecution claimed that Michél netted more than $100 million from his association with Low. When I ask if that figure is accurate, he declines to comment. In 2020, a year after Michél was charged, the feds offered him a plea deal. But he turned it down, maintaining that he did nothing wrong. For his part, Higginbotham pleaded guilty to conspiracy to deceive U.S. banks about millions of dollars in foreign lobbying funds and was sentenced to three months’ probation. He testified against Michél. As for some of the other characters in the sprawling narrative, Guo was convicted in the U.S. of defrauding investors and supporters of $1 billion.

“When the feds went into his $30 million apartment on Park Avenue, the apartment was remotely blown up. Did you know that?” Michél says, awestruck. “I guess all the evidence was in the apartment. Whatever. Allegedly, it wasn’t him [who detonated the bomb], but somebody blew the apartment up remotely while the feds were coming in.” (The FBI and the New York Fire Department reportedly were investigating a mysterious 2023 fire that broke out as authorities entered the luxury abode.)

Meanwhile, a court in China sentenced Sun to death in 2022 for taking bribes, with the chance that the sentence be reduced to life in prison without parole. Low escaped the United States and is believed to be living in China.

“He has as much freedom as someone in a phone booth,” Michél says of the man who turned his life upside down. “Without getting too philosophical about it, it was about me being at the right place at the wrong time. Or the wrong place at the right time.”

By the time Michél’s trial began, it appeared as though he had hired the wrong attorney in David Kenner, best known for representing Suge Knight in his 2015 murder case. He had little experience with white-collar crime. He allowed Michél to testify, an unorthodox move that rarely helps a defendant. In an absurd twist, Kenner reportedly used an AI-generated closing argument. “The court has adjudicated those three issues, and they have been denied,” Kenner says. (Earlier this year, Kenner pleaded guilty to misdemeanor criminal contempt and was sentenced to one year of probation over his handling of discovery materials in Michél’s case.)

Michél is now represented by Peter Zeidenberg. “We continue to believe that Mr. Michél was not afforded a fair trial, and that the jury’s verdict should be overturned,” Zeidenberg says. “We plan to appeal this verdict and believe that Mr. Michél will, ultimately, be fully exonerated.”

The story seems ripe for the Hollywood treatment, and at least three books on the subject are already in the works. Idris Elba has also approached Michél’s camp about acquiring his life rights, and there will be a documentary centering on Michél’s Zelig-like involvement in the surreal story. Director Ben Patterson unveiled footage of the project during a secret screening at the Toronto Film Festival in September. The audience sat in stunned silence, he says. Some of it was shot by Michél, who was brave (or crazy) enough to keep his camera on during the meeting with Sun in China.

“There’s so many people that were connected to this,” Patterson says. “It just is surprising and appalling that Pras is the one that gets singled out to the extent that he has. But in doing so, he exposed a lot about how government, celebrity and global finance are all intertwined.”

As Michél sits inside the place that he will call home for at least a few more months, he reflects on the people who abandoned him. No publicist would touch him or his case, fearing that they, too, would become entangled in a criminal investigation. Erica Dumas, a crisis publicist with D.C. ties who once worked for Sen. John Kerry, was the only one who would agree to work with him. Friends also began to keep their distance.

In 2020, right before the pandemic hit, two federal agents visit the L.A. home of one of his closest buddies, who is married with three daughters.

“Look, you get a call, FBI show up to your place, I don’t care who you are, your heart is going up your throat,” he says. “They’re like, ‘Hey, we just got a couple of questions for you. So can we come in?’ Who’s going to say no? So he let them in. The wife comes, sits in the living room, don’t know what’s going on, but she’s scared. And at some point, one of the agents goes, ‘What’s that? Do you smell that?’ The wife defecated on herself. She was that scared. And the wife later told my friend, ‘If you ever speak to Pras again, I’ll take my three daughters and you’ll never see us again.’”

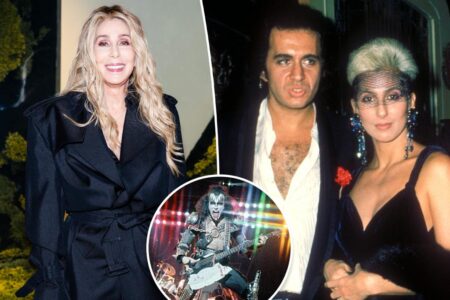

The Fugees at Sony NYC on January 28, 1994. (L-R) Wyclef Jean, Lauryn Hill, Pras Michel. (Photo by David Corio/Redferns)

David Corio/Redferns

And though he doesn’t say their names, it’s apparent that his former Fugees bandmates Lauryn Hill and Wyclef Jean are among those who ghosted him.

“I’m done with that. They’re going to Europe [to tour]. I can’t go, so,” he says of the conditions of his bail that prevent him from leaving the country. “It’s what it is. You can’t give people that kind of energy. So you could be frustrated, you could be disappointed, but I really believe in my path and in my journey, and I believe what’s mine, no one’s going to be able to take it away from me. So it’s better that you have a small group of people who really believe in you and believe in what you’re doing than to have 100 people around you, and the minute something happens — boom. People just disappear.”

A few weeks after our meeting, Michél files a blistering lawsuit against Hill, accusing her of fraud and breach of contract over the Fugees’ 2023 reunion tour that ended abruptly this year amid a slew of canceled concerts. It left little doubt about his feelings toward his former colleague. (In the shade-filled complaint, he claimed Hill showed “arrogance” for “unilaterally” rejecting a $5 million offer to play Coachella, alleging her “ego was bruised” because No Doubt got top billing over the Fugees. Hill hit back, calling the lawsuit “baseless” and “full of false claims and unwarranted attacks.”)

Michél makes his way to the baby grand. He’s thinking about his 6-year-old daughter. For most of our interview, he speaks flatly, seeming both resigned and exhausted. But he grows animated as he begins talking about the girl he calls “my joy.” She lives part of the year in Italy, making it difficult to see her given that he has to stay in the U.S. But she traveled to Los Angeles with her mother recently, giving him renewed hope. Over the past few days, a song lodged in his head like an earworm. He didn’t know how to play it, so he taught himself.

As the midday sun breaks through the clouds, Michél begins tapping out an unmistakable melody on the piano. It’s the Jackson 5’s “I’ll Be There.”

Read the full article here