“The shark’s not working.”

For weeks, the cast and crew of “Jaws” kept hearing the same four words over their walkie-talkies while shooting the film’s climactic ocean battle. That familiar message terrified Steven Spielberg, 27 years old at the time, with only one theatrical feature to his name. If one of the production’s three animatronic great whites broke down, it could mean another wasted day. All the setbacks put the film more than 100 days behind schedule and doubled its budget to $8 million.

“We didn’t know how they were ever going to finish this movie,” remembers Jeffrey Kramer, who played a sheriff’s deputy in the film. “There were rumors all around the set that the studio was going to shut us down.”

Spielberg, who had been entrusted with turning Peter Benchley’s bestselling novel about a rampaging shark into a cinematic event, feared he’d be fired. Yet he was determined not to betray how much the pressure weighed on him.

“His nails were bitten to the stubs,” remembers Carl Gottlieb, the film’s co-writer. “But that was the only manifestation of his nerves. Steven knew he needed to lead by example. That meant concentrating on his job and keeping his cool even when everything around him was going to hell.”

And everything that could go to hell, did. Filming just off Martha’s Vineyard had been Spielberg’s idea. He thought making “Jaws” on the open water would give it authenticity. It turned out to be an agonizing ordeal. Boats filled with pleasure cruisers drifted into shots; the waves and weather were unpredictable, so maintaining continuity was nearly impossible; and everyone kept getting seasick. When they weren’t retching over the side of the boat, the actors often clashed, with hard-drinking veteran Robert Shaw, playing fisherman Quint, frequently belittling Richard Dreyfuss, the up-and-coming actor cast as Hooper, a cocky oceanographer. The whole enterprise seemed doomed.

“’Jaws’ should never have been made,” Spielberg admitted to Time the Monday after the film opened in 1975. “It was,” he said, “an impossible effort.”

Despite its chaotic creation, “Jaws” became the highest-grossing movie in history, earning a staggering $260.7 million in its initial release. Fifty years later, we’re still living in the entertainment landscape that “Jaws” reshaped. Its outsize success made studios realize that if they packaged and promoted movies correctly, they wouldn’t just be hits — they could become phenomena, selling T-shirts and toys along with tickets. “Jaws” established the template for “Star Wars,” “Jurassic Park,” “The Avengers” and the other culture-defining smashes that followed in its wake.

“This movie changed cinema, and you still can’t go to a summer blockbuster or to the beach without thinking about it,” says Eli Roth, the director of the horror film “Hostel.” “So much of the language of cinema comes from this film. [Spielberg] created all of it.”

Top, Part of a storyboard; bottom, a shot from “Jaws”

mptvimages.com; Everett Collection

“Jaws” is a masterpiece, rivaling “Psycho” in its use of editing, music and camera angles to establish tension and suspense. The film works because it taps into familiar anxieties. Who hasn’t felt suddenly paranoid about all the creatures lurking beneath the waves? But the irresistible force of Spielberg’s vision and ambition allowed him not only to finish “Jaws,” but to create something far greater than the sum of its potboiler parts.

“It’s a great story of what Steven Spielberg accomplished by surviving what was a nightmare,” Steven Soderbergh says. “If that person hadn’t made it, it probably wouldn’t have been made at all. It certainly wouldn’t be a classic.”

And it continues to inspire artists who were born decades after “Jaws” opened. “When directors bring us ideas, ‘Jaws’ is still referenced as much as any other movie,” says Jason Blum, founder of Blumhouse, the company behind “The Purge” and “Get Out.” “Even young filmmakers say, ‘It’s going to be like the shark in “Jaws.”’ That’s incredible for a film that’s 50 years old.”

No one would be more surprised by the enduring appeal of “Jaws” than the Universal executives who greenlit the picture. Initially the studio treated the film as just another B movie. “Nobody thought much about it,” says Joe Alves, the production designer. “People at Universal were much more excited about this George C. Scott film called ‘The Hindenburg.’”

As word leaked out in the Hollywood trades about the delays and cost overruns, there was a growing sense that “Jaws” had all the makings of a disaster. “Everywhere we went, people treated us with sympathy, like we had some kind of illness,” David Brown, one of the film’s producers, told Variety three weeks before “Jaws” debuted. “They’d say, ‘I hope you overcome your difficulties.’”

But after the film was finished and started testing, preview audiences were electrified by what Spielberg delivered; they screamed so intensely that popcorn flew out of buckets. “As soon as the studio saw that reaction, they went, ‘Jesus, this is going to be a big movie,’” remembers Alves. “That’s when everything shifted.”

Suddenly Universal was inspired to back the picture with a massive (for its time) $1.8 million promotional blitz, one that revolutionized how movies were marketed and released. It started with the decision to debut the film on June 20, 1975. Nowadays, summer is the most popular time for moviegoing, but before “Jaws,” studios hadn’t yet become obsessed with that season. Many of the biggest films — including “The Godfather,” “Love Story” and “The Exorcist” — premiered in the spring or winter. But those were aimed at adults; “Jaws” wanted to attract teenagers along with their parents, so it helped to debut the film when school was out. The film’s huge gross illustrated the commercial power of this younger audience. It was a lesson Hollywood would never forget.

Crowds lined up outside a movie house in New York City to see “Jaws” when it opened in June 1975.

Bettmann Archive

“Jaws” also demonstrated how a movie could be turned into a zeitgeist-tapping sensation through the power of mass-marketing and distribution. “Jaws” went national, with Universal releasing the movie in more than 400 theaters across the country. Studios were still employing a road-show model for many films, rolling them out slowly across different markets and advertising in local papers and TV stations along the way. But Universal wanted “Jaws” to be easily accessible to everyone in America all at once, so it could become an event. To generate excitement, the studio invested heavily in television spots, airing dozens of 30-second commercials on primetime network shows like “The Waltons” and “Happy Days.”

The company also leaned into the popularity of Benchley’s novel, which was released in 1974, coordinating with the publisher so the marketing campaigns for the movie and the book that inspired it would be aligned. That ensured that the “Jaws” film would arrive with “pre-awareness” — meaning that audiences would already be primed for the carnage in store.

“We sent copies to people who talk to other people, like headwaiters and cab drivers,” Brown told Variety in 1975. “We adapted the artwork of the book to the artwork of the film promotion. By the time we sneaked the film in Dallas, we didn’t even need to name it in the ad. We put in the logo of the shark’s teeth and the swimming girl and 3,000 came out in a hailstorm.”

“Jaws” is a bridge between the darker, moodier stories that dominated late ’60s and early ’70s Hollywood, such as “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The French Connection,” and the blockbuster era that followed. In some ways, the two halves of its story connect those two distinct periods in cinema history. The first part of “Jaws” follows ineffectual police chief Brody (Roy Scheider) as he tries and largely fails to resist political pressure from the mayor (Murray Hamilton) to keep the beaches open, even as the body count rises. It’s a portrait of how institutional corruption can lead to bloodshed. That resonated with viewers who lived through the Vietnam War, and it was very much in keeping with the skeptical tone of the movies that immediately preceded it.

“You could feel this malaise and cynicism start to seep into movies in the late ’60s. You had the war and the hippie movement and then Watergate,” says Kevin Sandler, associate professor of film and

media studies at Arizona State University. “Movies reflected that for a while. But by the mid-’70s tastes were shifting, and people wanted things that were less politically aware and purely entertaining.”

The second half of “Jaws” taps into that desire for escapism, leaning into spectacle and helping to establish the blockbuster formula in the process. As soon as Brody, Quint and Hooper embark on a quest to kill the shark, the picture assumes a narrative propulsion that Spielberg understood innately. He instructed Gottlieb to streamline Benchley’s novel, casting aside subplots such as an affair between Dreyfuss’ character and Brody’s wife, as well as a real estate conspiracy involving the Mafia.

“He wanted to eliminate everything that was extraneous so we could be totally focused on the story of three men against the sea,” says Gottlieb.

Spielberg also knew that the movie’s villain needed to have a gargantuan size and scope that would make it truly terrifying.

“The way Peter wrote the book was that this was just a normal shark doing what normal sharks do, so he kept urging Steven to keep the shark down to 15 feet,” says Wendy Benchley, the author’s widow. “But Steven understood movies; he knew that he needed the shark to be 25 feet so it could be this monster who could swallow Robert Shaw whole.”

Initially, the great white was supposed to have even more screen time. However, the mechanical difficulties meant that Spielberg had to shoot around the shark, finding novel ways to suggest its deadly presence. To keep audiences off guard, he relied on creative editing by Verna Fields, who cut together shots from the fish’s perspective with glimpses of a fin cutting through the water and set them to John Williams’ pounding and foreboding three-note theme. That iconic music, partially inspired by the score that plays during “Psycho’s” shower scene, took Spielberg a second to embrace.

“I played boom boom boom on the piano for him,” Williams told Variety in 2024, “and Steven said, ‘Are you serious?’ I said, ‘If you hear the basses and celli in the orchestra, I think it might work.’ And so we did a session with the orchestra, and he said, ‘Oh, this is wonderful.’”

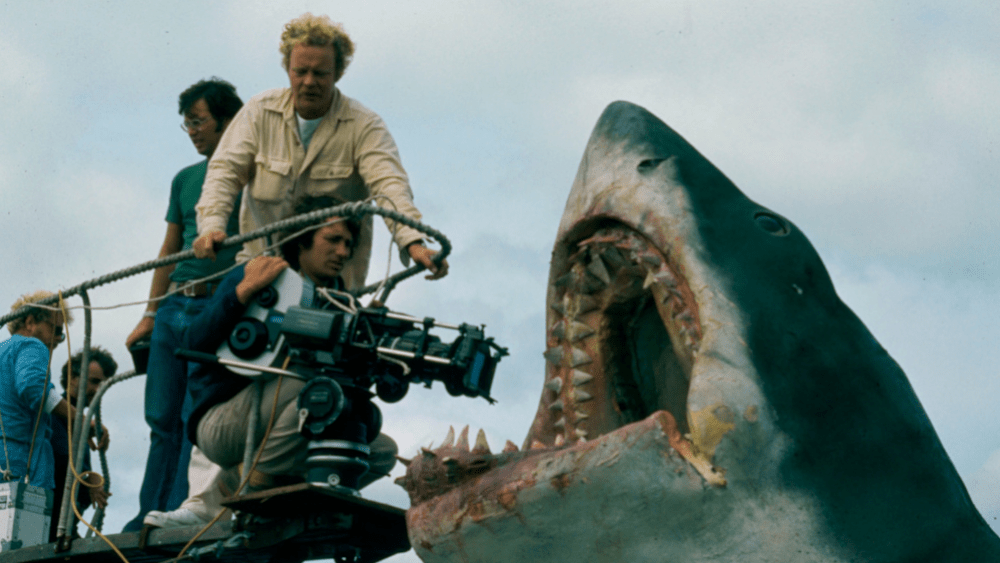

Spielberg on one of three animatronic great white sharks used in the filming of “Jaws”

Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

In 1975, when the shark finally leaped out of the ocean, crashed into the ship and sank his teeth into Quint, audiences were as dazzled as they were terrified. Today, the effects seem primitive. What resonates most strongly is the film’s subtler or more emotional moments — the camera lingering on a man left holding a stick after his dog fails to come back from a swim or the scene where Brody’s son mimics his depressed father’s body language at the dinner table. And, of course, there’s Quint’s USS Indianapolis monologue, an aria of trauma and suffering, in which he drunkenly describes watching his fellow sailors get ripped apart by ravenous tiger sharks after their cruiser sinks. The speech was honed by various writers, including Gottlieb, Gloria Katz and John Milius, but it was Shaw, a playwright as well as an actor, who finally cracked it.

“He took all the versions to his house,” Gottlieb remembers. “Then he came to dinner one night, slammed his hand on the table and said, ‘I’ve got that pesky speech licked.’ He read it to us. It was so stunning that when he finished, Steven said, ‘That’s it. We’re shooting that.’”

The entire monologue lasts roughly four minutes, an eternity in an era of quick-cutting superhero films and fantasies. But it is essential in establishing the bond between the three protagonists, so that audiences will actually care if they live or die. The villain may be fantastical, but the drama still operates at a human level. That sensibility has been lost in the ensuing decades as the blockbusters that “Jaws” inspired have become more obsessed with establishing cinematic universes than creating compelling characters to inhabit them.

As for Spielberg, “Jaws” launched his career into the stratosphere. Public fascination with the wunderkind filmmaker intensified as the film dominated the box office. The attention Spielberg received was flattering but came with its own pressures.

“I don’t think I’ll ever top ‘Jaws’ commercially,” Spielberg said in a 1977 New York Times profile shortly before the release of his next film, “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” “The minute ‘Jaws’ became so successful, people kept saying, ‘How can you top that?’ But I don’t run my career on what people think.”

Spielberg was wrong about one thing. Two of his films, “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial” and “Jurassic Park,” would become the most commercially successful in history, before they too were supplanted by even bigger blockbusters. As for the director, he would move beyond his populist roots to examine bleak moments in history with his masterworks “Schindler’s List” and “Saving Private Ryan.” As an artist, Spielberg kept stretching, telling bolder and more challenging stories — as long as they took place on land.

“You’ve probably noticed I haven’t done very many water pictures since ‘Jaws,’” Spielberg told biographer Richard Schickel in 2024.

“Jaws” left even its director terrified of the ocean.

Read the full article here