Just asking: Has Donald Trump been spending time scrolling through MGM+ lately?

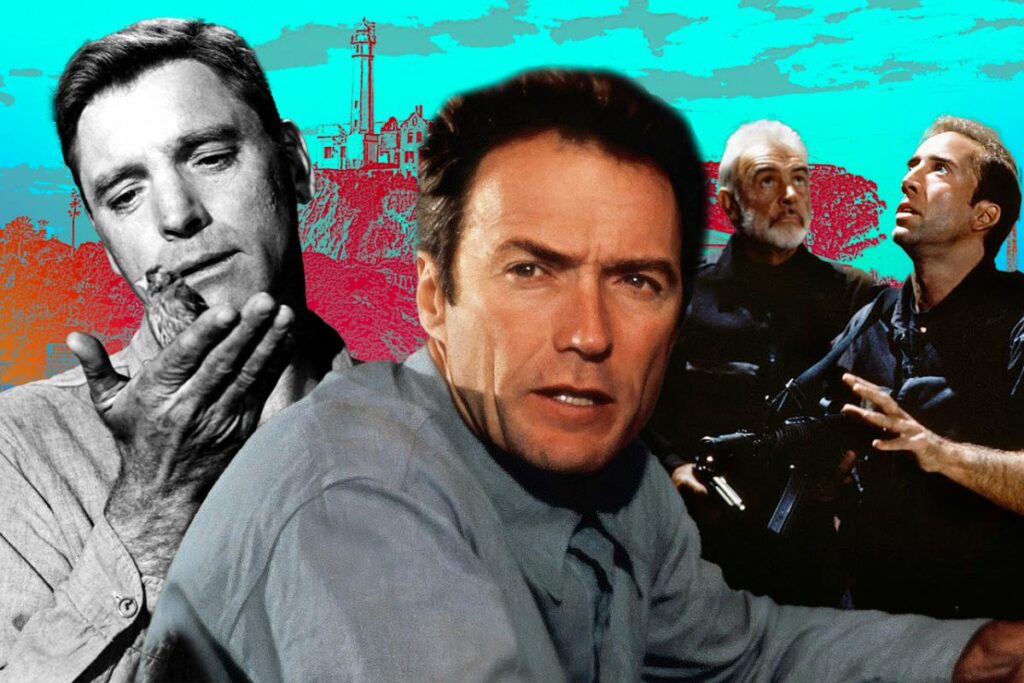

It seems unlikely that a movie-focused streaming service would break the stranglehold that cable news holds over this man. Yet the fact that the service is currently streaming the three best-known movies about the old San Franscisco island prison Alcatraz – Birdman of Alcatraz, Escape from Alcatraz, and The Rock – seems like as good an explanation as any for why Trump has ordered the re-opening of the infamous island prison after decades of dormancy. Of course, attentive or even passive viewing of these movies doesn’t make much of a case for Alcatraz as a beacon of the “law and order” the president loves to fantasize about; then again, Trump has never shown much attention span, so maybe he’s thinking only of the venue’s general notoriety.

The movies themselves share some interesting connections, daisy-chained across 17-year intervals. The first, 1962’s Birdman of Alcatraz, is a prisoner’s biography that portrays the prison as oppositional to the rehabilitation of its occupants, released a year before the facility’s 1963 closing. The same year as the film’s release saw the real-life breakout of three inmates, which was fictionalized for 1979’s Clint Eastwood vehicle Escape from Alcatraz. Doubtless that film and the overall Alcatraz legend was front of mind when making 1996’s The Rock, about a mission to break into the prison and free hostages that have been taken there in its capacity as a museum. Sadly, no new Alcatraz-themed movie was released on schedule in 2013; that year, a future version was merely destroyed at one point during Star Trek Into Darkness.

All three movies in the unofficial Alcatraz trilogy are worth watching, though it’s the Eastwood film that spends the most screen time there. In Birdman of Alcatraz, Robert Stroud (Burt Lancaster) becomes known as the Birdman because he saves and cares for a baby sparrow, turning that tenderness into an ongoing hobby, and inspiring other prisoners to do the same – but this all happens at Leavenworth Prison, and when he is transferred to Alcatraz, he’s not allowed to continue his work (despite having published a book on bird diseases). The Rock, meanwhile, spends a lot of time setting up and planning the big break-in; it’s a Michael Bay movie, so there’s a big car-chase scene through the streets of San Francisco involving a bright yellow convertible before anyone is snaking around the considerably less sexy prison tunnels.

Escape from Alcatraz, however, starts with a prisoner’s intake and doesn’t stop until Frank Morris (Eastwood) and his accomplices are free. (Speaking of free: Escape From Alcatraz is currently available to stream on PlutoTV, but you’ll have to put up with commercials.) Perhaps two of its 110 minutes are spent off the island. Not all of the movie was shot there, but chunks of it were, and in fact the production paid for several permanent restorations to the facility. This was Eastwood’s fifth and final movie with his mentor and collaborator Don Siegel, toward the end of Siegel’s career. He made just two more movies after this one, then retired; a dispute over whose production company would make the movie ended the Eastwood/Siegel working relationship on a bum note.

The movie itself, though, remains a terrific prison-break thriller. Like some other Siegel movies, it’s somehow both quietly procedural and taut with tension (there’s hardly any dialogue in the final break-out sequence), full of clear, unfussy characterizations and compositions. In this particular case, there’s something elemental in its refusal to consider much action beyond the prison walls, a setting that calls back to a quarter-century earlier in Siegel’s career, when he made the black-and-white prison noir Riot in Cell Block 11. If anything, despite releasing at a far more permissive time, Alcatraz is less brutal in its violence than the earlier picture; its one gory moment is a self-mutilation made in protest and despair.

Indeed, apart from one token threat from a creep who Eastwood dispatches, not much is done to pump up the criminal bona fides of the inmates. Tying to Birdman of Alcatraz, which was made around the time this movie is set, Escape makes it clear that at least some of these people have been transferred here punitively after beginning their sentences elsewhere, letting the prison’s reputation precede it. That is to say, it’s more threat than necessity. One inmate is there because he drove a stolen car across state lines, a technicality that turned his repeat transgression federal. Eastwood’s Frank Morris is better-known for escaping other prisons than for any particularly nasty crimes against his fellow man.

Even the escape plan itself is depicted as more of a precautionary measure. While other inmates are shown to be mistreated by a prison administration that removes small but lifesaving privileges for petty reasons, Frank and his old friends the Anglin brothers (Jack Thibeau and a young Fred Ward) want to break out mainly because they see an opportunity to avoid being subjected to a lifetime of prison drudgery, where any efforts to better themselves are treated as incidental at best. They’re not in any immediate danger from some collection of worst-of-the-worst hardened criminals, or even relentless cruelty from the guards; they’re staring down the inherent inhumanity of prison itself.

It’s strange, then, that anyone whose images are clearly formed more from common cultural misconceptions and paranoia more than any genuine expertise would look at Alcatraz as a symbol of law enforcement at its finest. These movies all make it more of a physical or mental gauntlet than a marvel of criminal containment; that’s even true of The Rock, the only one of the three not to turn specifically sympathy for Alcatraz prisoners over their captors. And Sean Connery’s character is, of course, an ex-prisoner, designated by the movie’s rewritten history as the “only man” to escape Alcatraz. Even then, he’s been duly recaptured, then re-imprisoned without trial. Michael Bay’s politics are like a funhouse-mirror warping of Eastwood and Siegel’s institution-skeptical, vaguely libertarian, yet often community-minded leanings; he loves flouting authority while also insisting that individual might makes right. (We’re essentially prompted to feel that Connery’s John Patrick Mason deserves freedom because he’s the best, not because he was illegally held for decades.)

In real life, no one is sure what happened to the three prisoners who did break out of Alcatraz, inspiring the Eastwood movie; the initial assumption that they drowned in the bay has been challenged, and the film plays up the ambiguity, strongly implying that they may have made it out. The prison itself was closed because of the enormous cost of maintaining an island prison, not because of the recent escape, but those two facts together do feel extra-symbolic: If the main takeaway from the expensive maintenance Alcatraz was the impossibility of escape, and three guys may have successfully escaped, then, well, what’s all that money for? Ultimately, perhaps it makes more sense as a movie set than as one more functioning prison in an incarceration-addicted country. Trump may see the island as a symbol, but all three movies in the Alcatraz trilogy make it pretty clear that it’s not the symbol in his head.

Jesse Hassenger (@rockmarooned) is a writer living in Brooklyn podcasting at www.sportsalcohol.com. He’s a regular contributor to The A.V. Club, Polygon, and The Week, among others.

Stream Escape from Alcatraz on Fawesome

Read the full article here