They say the devil’s in the details, and with “Sinners,” Oscar-winning production designer Hannah Beachler paid special attention to every cloud of dust that rolled onto the set.

As soon as Ryan Coogler told her he was writing the script, Beachler began researching. The director had just done the Blues Trail through the Mississippi Delta, talking to blues artists and learning the history behind the music, so Beachler decided to do the same. “I wanted to be there talking to older generations and younger generations. We met a couple of owners of some juke joints, and [learned] what the vernacular and the architecture were,” she tells Variety, explaining that much of the trip was about observation. “What are the things that I’m noticing?”

Beachler noticed she could drive for 30 minutes and not see another car. On the drive, she noticed a field and drove through it, traveling for at least a mile before coming across a small church. “There was nothing around it but big blue sky and cotton fields,” Beachler recalls. That detail later shows up in the film as she designed the farmhouse-style chapel. Amid all that, she placed easter eggs that honored her past work, namely “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever,” and the history and legacy of African folklore, and of course, the blues.

“Sinners” is more than a great vampire movie; it speaks to folklore, spirituality, history and culture. Michael B. Jordan stars as twin brothers Smoke and Stack, who return home to Clarksdale, Mississippi. They plan to open a juke joint and recruit their cousin Sammie, played by Miles Caton, to come jam. But Sammie doesn’t just have a gift for music; his voice is otherworldly and draws out the supernatural beings within the town, who want to stake their claim to him.

The supernatural is what made the film thrilling for Beachler, as she considered how to embed those themes in her set designs. “Ryan gave us space to put a piece of ourselves in it, whether that comes in the form of an easter egg or something that I’ve been inspired by or an homage. I want to pay homage to something that I feel is important to the community,” Beachler says.

Here, she breaks down the film’s key sets as they recreated Downtown Clarksdale, Miss., the local church, Annie’s home and Smoke and Stack’s juke joint, and why they were important to her. She teases the “Black Panther 2” and Howlin’ Wolf easter eggs. But for Beachler, it was all about the detail, and what was within that, and what it spoke to.

Downtown Clarksdale

When Smoke and Stack return, one of the first places they head to is downtown Clarksdale, Miss. It’s where they spread their message about the juke joint, and where they get their supplies. This was shot in Donaldsonville, La. Beachler had “three to four weeks, which was unheard of,” to create a whole block. Every road needed to be dirt instead of paved, so the dirt was brought in by the truckload. More importantly, each side of the street was a reflection of their segregated town.

“When you go into downtown in our film, you’ll see that King Tamales is one of the stores right next to the grocery store. I started really learning and talking to the people about the history of tamales, because it’s a big deal in the Delta, and that’s not two things you’d put together, the Mississippi Delta and tamales.

“Different cultures played a big part in the film. I wanted to include Red Hots and King Tamales, things that are part of their history,” Beachler says.

“Ryan wanted to divide the street with one side being black and one side being white. We were really influenced by Min Sang of Clarksdale from that era, and that was a Chinese American grocer in Clarksdale around that time. So there’s a lot of what Clarksdale is in the train station and in downtown, and not just coming up with what we think it is, but what it actually was. If you look at the window, it tells you about where you are.

“If you notice in the two grocery stores, one is the Black grocery store owned by Bo and Grace Chow. In that, you’ll notice that it’s all produce. It’s all working things to buy like hoses, brooms, buckets and mops. If somebody wanted you to be their maid, you had to be their maid. That was just the way that it was. So it’s all about the work. The candy on the Black side is hard, but when you get to the white side, there are cakes, fruit, and there’s more advertising. Those are the small, subtle differences between those two sides. Even when you walk up to the stores and see the exteriors, you’ll see that there’s a similarity in the signs because it was done by Grace. If she were living today, she would be an artist. So that comes out in the signs and you’ll see that they’re very specific in the way that the language of those signs is to her. A lot of that was inspired by Chinese graphics from the 1920s in Shanghai.

“We really wanted to make those subtle differences between the two places, of what you see on each side and understand the differences in that Jim Crow era. On the white side, you’ll see that they have a car dealership and a movie theater, whereas on the Black side you’ve got the tamale store and a little tiny cafe, where you’ve got a really nice cafe on the other side.”

The Church

“This is one of my absolute favorite sets, and that, with the juke joint and Annie’s, were the first three things that I designed. I jumped in and I don’t know if I was possessed or something, but I started doing all my research and really looking at a lot of (writer) Eudora Welty, who is a fabulous photographer from the Delta during that same time period. I grabbed my sketchbook, and the first things I sketched were what ended up in the film. But the church became very much about several different things that Ryan talked to me about, but mostly about the representation of that holiness and that purity that you find in juxtaposition to the outright hedonism and capitalism of the juke joint.

“We have an X-shaped cross in the rafters, and it was homage to ‘Black Panther: Wakanda Forever’ and Chadwick Boseman because it was doing the Wakandan gesture in the beams. And that cross followed certain characters around.

“There’s also the three crosses that absolutely stand for the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. When Sammie (Miles Caton) and Jedidiah (Saul Williams) are standing under it, they are the father and the son, so they’re the fourth cross. When Sammie walks in holding the bit of guitar, he walks directly under the cross. I wanted them between that and it to be a juxtaposition to this veil that’s been opened, and that they’re standing in this very spiritual space together, where Sammie has a decision to make. Also, the crosses are exactly 33 inches apart, which is the age, and also the symbolism of when Jesus died.”

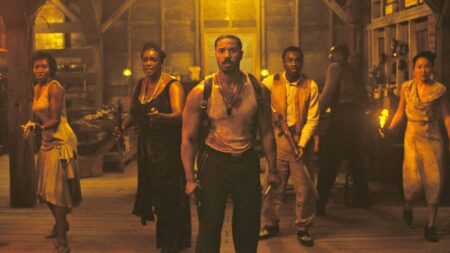

The Juke Joint

The juke joint could be seen as the heart of “Sinners.” It’s where music and spirituality come together, it’s where the action unfolds.

Beachler had eight weeks to build two juke joints, one for interior shoots and another for exterior shoots. It was all about the detail and process Beachler went through. “We used boric acid to rust the sheets of metal outside the juke joint,” Beachler reveals.

While the process took longer, Beachler wanted everything to feel as real and authentic as possible, so everything needed to be real, including the rust.

“One of the things, and I’m not going to say which things, I’ll eventually say what it is exactly, but I want people to see it again and see if they can find, there’s a representation in the juke joint for every environment that we visited on the way to to it. So there’s a representation of Annie’s oak trees that sort of protect and cover her home in the juke joint that protects and covers them.

“In the third act, the white wall where Mary (Hailee Steinfeld) bites Stack (Michael B. Jordan), that is the representation of the white church, and there are horizontal lines above people’s heads, specifically Stack and the vampires, I should say, within that.

“When you first see the place, the colorway with Hogwood, the mill owner, it feels very much like old wood, but as it turns into the juke joint, we changed the bottoms of everything to rough-sawn wood. What happens is that wood is wet and it shrinks, and that’s what they built with. As we filmed, it started shrinking up, and we would put dust on it. We didn’t put anything underneath it, so it would bounce. When they were doing the scene with Jamie Lawson, and she’s singing and you see everybody smacking the floor, that floor was bouncing and the dust was coming up and it was making it a little bit more atmospheric. It really lent itself to the sound, to the atmosphere that it created when the extras came in and we’re doing that sultry juke joint dancing.”

“There are a ton of easter eggs, and I’ll tell you in the juke joint, on the back wall where the entrance is, and you’ll see the rusted tin inside of that juke joint. And if you were to play ‘Smokestack Lightning by Howlin’ Wolf and you were playing it on a tape recorder and you stopped it in the chorus and you looked at the equalizer where all the bars stop, we painted that in on the back rust wall. So that chorus sort of lived in the juke joint and over everyone.

“I think they say it at the end, ‘For that one day we were free,’ and that’s really what it was. It was the story of the sun, and with that, that was our inspiration for Sergio Leone. I love a Western, and that’s something Ryan and I have greatly in common. I would watch Westerns nonstop when I was young. So you have some ‘Stagecoach’ and ‘The Searchers,’ ‘Chisum’ and Leone’s trilogy, all of that is in there.”

Annie’s Home

SINNERS, Wunmi Mosaku, 2025. © Warner Bros. / Courtesy Everett Collection

©Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett C

When building Annie’s home, Beachler was inspired by a photograph she had seen. Something struck her about the woman and how she stood. Beachler wanted to use haint blue for Annie’s home, a protective light blue inspired by the Gullah Geechee people and enslaved Africans who used that shade of blue to protect themselves from evil spirits.

“Annie served the community even though she was on a plantation, both spiritually and as far as selling to the workers, and I wanted to make her feel like she was the protector in that place. She was the one that you could go to if you needed to heal.”

“In some way, it’s one of the first images that I was looking at in the research, and it was the sharecropper home with this mound of cotton just on the porch. There was a woman standing outside, and there was just something about that image in that small home leaning to one side in this massive field that it just spoke to me immediately. It said everything to me about that time in that place, the hard life and the meager living situation. But this woman had on this beautiful dress and a hat, and there was something about her that still had this dignity and beauty in front of all of this, what you would say is in abject poverty. Annie was strong, and I felt that from this woman in this image.

“I wanted to put the ‘haint blue’ in her world because it’s such a protective color. We hung little prayer cards all up in the rafters, and when they were rehearsing, one of the prayer cards fell and Michael caught it, and it said, ‘You are where you’re supposed to be.’

“We had a Hoodoo expert come in and work with us about some of her rituals – Hoodoo is a practice of spirituality – and all of that was in there. And overnight, we had these weevils that make these beautiful patterns, and they were just everywhere. It was just the perfect place. That was the spot, but we almost didn’t get it. But I kept pushing and pushing and pushing, and we got that location.

“I also wanted to sort of juxtapose her against what I think a lot of Black women go through, still to this day, if you’re a strong woman, you’re seen in a certain light, or all of these stereotypes that come with that. The plantations didn’t go away when slavery stopped. It was just a different way of enslaving people during sharecropping time and Jim Crow, so Annie’s was something that was just sort of a heart and soul set for me.”

Read the full article here