Sometimes the best stories are worth the wait.

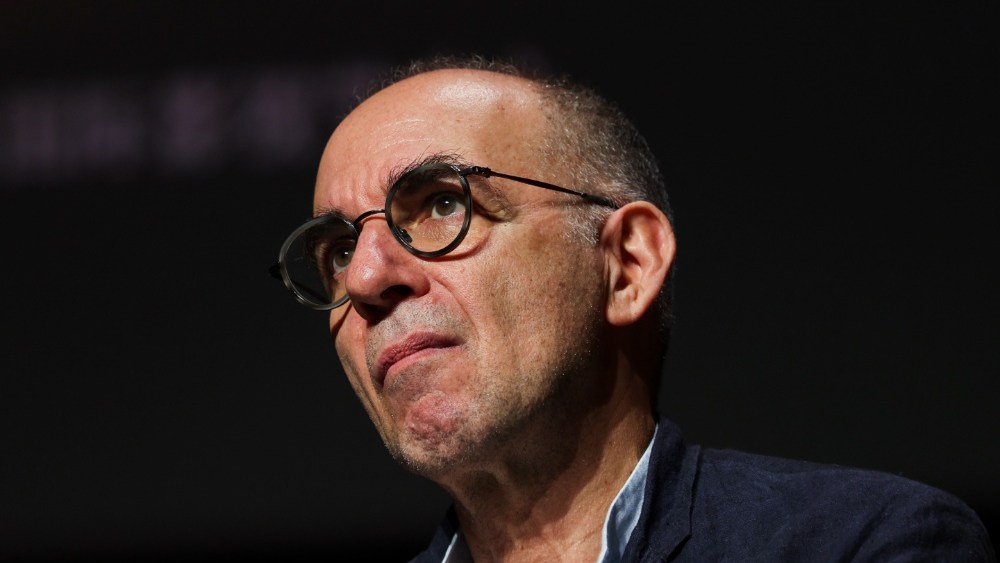

Giuseppe Tornatore revealed at a Shanghai International Film Festival masterclass that his beloved Oscar-winning film “Cinema Paradiso” gestated for 11 years before he wrote a single word.

“When I made my first film about the Mafia [“The Professor”], I was already brewing the script for ‘Cinema Paradiso’ in my mind,” Tornatore explained to film scholar Marco Müeller during the conversation at Shanghai, where he served as the head of the main competition jury. “It took 11 years of contemplation before I actually started writing the script.”

When he finally put pen to paper after more than a decade of contemplation, the script poured out in just two and a half months. “I had been thinking about this story for 11 years,” he said. “Once I started writing, it felt like the story was already complete in my mind.”

The evening followed a screening of “Cinema Paradiso,” with Tornatore weaving together memories of his Sicilian childhood and reflections on storytelling that spans decades. He later revealed a serendipitous encounter that validated his creative process.

“After this film was completed, I once met the author of ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude,’” Tornatore recounted. “During our conversation, Gabriel García Márquez said something to me: when you start brewing a story in your mind, don’t write it immediately, just think about it — the more you think, the richer the story becomes.”

The director’s relationship with his material runs deeper than mere narrative craft — the film draws directly from his own childhood encounters with cinema magic. “I saw these giant close-ups on the screen and kept wondering where these people came from,” Tornatore recalled of his first cinema experience at age six or seven. “During intermission, when the lights came on, these people would disappear. I was constantly asking myself: where do they come from and where do they go?”

That childhood curiosity led him to befriend the local projectionist, who taught him both technical skills and photography. By age 14, Tornatore was working as a projectionist while attending school, studying editing by examining film strips during projection.

“I learned that film editing is truly crucial work,” he said. “I tell all film students: don’t limit yourself to learning just one thing. Learn multiple aspects, especially editing, because editing is extremely important.”

This hands-on apprenticeship shaped Tornatore’s filmmaking approach. He continues editing most of his films personally, viewing it as essential to the creative process.

The conversation also revealed how Tornatore’s collaboration with legendary composer Ennio Morricone began in an unexpected political context. As a young man, he broke protocol at a political rally by playing Morricone’s score from “Sacco and Vanzetti” instead of traditional workers’ songs.

“That music symbolized equality and justice,” he explained. “It was perfect for the political gathering, even though it broke with convention.”

When addressing contemporary cinema challenges, particularly short-form content and changing viewing habits, Tornatore remained optimistic. “The number of films people can watch daily now compared to 50 years ago is dramatically higher,” he noted. “This gives me confidence in the film industry.”

However, he advocated for the theatrical experience: “I encourage young people to go to cinemas. The big screen and atmosphere you get there is completely different from other viewing methods.”

Throughout the evening, Tornatore emphasized staying true to artistic principles. When discussing his characters’ choices — Totò’s departure in “Cinema Paradiso” versus 1900’s decision to remain on the ship in “The Legend of 1900” — he stressed following one’s convictions.

“Maintaining your original intentions is extremely important,” Tornatore said. “Having principles as a person and sticking to those principles is crucial.”

The masterclass concluded with audience questions, including one from a film student who had watched “Cinema Paradiso” nine times. Tornatore’s response encapsulated his philosophy: “Every film I’ve made represents a part of my life. When I watch each film, it evokes memories of certain life experiences. I’ve never thought that I shouldn’t have made any particular film.”

For Tornatore, who maintains a schedule of watching three films per week, cinema remains a living art form. His five-day marathon viewing 12 competition films at Shanghai reminded him of his youth: “It brought back the feeling of when I was young and could watch two films a day.”

Read the full article here