“‘Normal sex.’ Who decides what that means? You early millennials are so tragic. You think sex is just penetration and orgasms. Why? Because that’s what Samantha said. Sex? Sex is a wave. Sex? Sex is a mindset. Sex is the nonlinear emergent phenomenon that arises when two or more beings, they touch energy fields.”

Did you get all that, class? If not, the notes are up on the student portal.

This huge gob of sex-positive pablum is hawk-tuah’d up by Sonya, Molly’s palliative care counselor. The whole time she’s talking about how sex is like a rainbow in the shape of the infinity symbol or whatever, I was sitting there thinking, “Not if you’re doing it right! Sex is the province of fucked-up perverts. Leave this crystal-energy don’t-yuck-your-yum bullshit for Obama-era webcomics and BuzzFeed personal essays — I’d almost rather fuck the guy who keeps demanding that Molly clasp his balls.” (Clasp, not cup. It’s an important distinction!)

Personal tastes aside, the problem with this kind of dialogue on Dying for Sex is an almost universal one when it comes to shows and films that use very direct therapeutic language to address their core conflicts. Simply put, that’s what we have therapy for. Fiction teaches us better by showing us how people behave and allowing us to reason out why for ourselves. Even on The Sopranos, Dr. Melfi’s insights were only ever half the equation; you had to see how Tony interpreted what she said and applied it, or didn’t, in his actual day-to-day life before drawing the lesson David Chase and company intended to impart in any given episode or storyline. You get a lot more out of that than you do from a fictional mental health professional simply describing best practices and calling it a day.

It’s especially galling in this episode, because until that point, Molly was teaching through example. She has that disastrous date with the ball-clasper (SNL’s Marcello Hernández), a 25 year old who seeks out older women for sex because, usually anyway, they know what they want and are more than willing to ask for it from him. Molly, by contrast, literally says she doesn’t know what she enjoys, leaving ball-clasping the order of the evening. It winds up not working for either of them, but the date gets her to thinking.

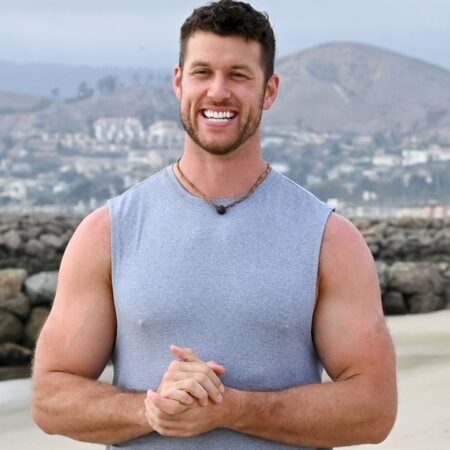

So do the living arrangements at her new apartment, where only thin walls separate her from her slovenly neighbor (Rob Delaney, whose role is billed only as “Neighbor Guy”). Though she’s disgusted by his personal hygiene and disregard for the cleanliness of common spaces, not to mention his extremely loud video game habit, she finds herself enormously turned on when she hears him masturbating. The fact that she hears him while she’s masturbating, which obviously implies he can hear her in turn, makes it all the hotter. And when you put aside the guacamole and sour cream he’s encrusted with, he’s a pretty good-looking guy, too.

Put it all together and you’ve got the recipe for some weird but hot self-actualization. When she orders him to pick up his trash, he does so, and they both quickly realize she gets off on giving him orders as much as he gets off on following them. A liaison rapidly unfolds in which Molly goes into his apartment and makes him masturbate in front of her while she insults his penis and makes other humiliating comments. Unfortunately, the unlikely duo take things a step too far when he begs her to literally kick him in the dick: She falls over in the process, badly injuring her leg, into which her cancer has metastasized. (That this show comes out as the Musk/Trump/RFKJR regime deliberately destroys cancer research in this country for reasons I can only characterize as “pure evil” is a whole different kind of kick in the dick.)

It’s while she’s in the hospital for her leg that Sonya gives her big speech, which follows a briefer riff with Nikki about how “pain is political, pleasure is political,” particularly regarding discrepancies in how women in general and Black women in particular are dealt with by doctors. These eminently true statements are, however, not favorably showcased by this kind of Very Special Episode didacticism. An earlier scene, in which Molly makes light of the vaginal dryness accompanying her medically induced menopause and the drug cocktail involved in bringing it about, is much more effective. Watching her talk to the doctor about the issue while doing a funny little Scotsman voice because she’s embarrassed, watching him write it off as a mental health issue — that’s making the point in a way that enlists the audience to derive meaning from what they’re watching, rather than writing the meaning out and speaking it directly at them.

Running parallel to all this is a Fight Club–style storyline, but in reverse: Molly fakes having a less severe illness than she actually has, in order to get into more fun support groups. She winds up getting fed a plot of power-of-positivity bullshit that comes to an abrupt end when she discloses the true extent of her illness: She gets kicked out of the group not for lying, but for being a bummer.

Again, this makes an argument without having to spell it out for us: The Secret–style positivity is no match for figuring out what gets you off and then, you know, getting off on it, hard and often. Take the powerfully orgasmic Nikki as an example: She loves sex so much in part because she can orgasm from vaginal intercourse alone. “I’m a real Penetration Patti,” she says, half-bragging.

Even as she says this, though, her own life is beginning to suffer from her obligations to Molly. Her sex life with her live-in boyfriend Noah has dried up, and she misses so many rehearsals — and is so checked out at the ones she attends — that she gets fired from the Shakespeare production she’s been so thrilled to be a part of. Will the show dig into the strain illness places on caretakers, and the way the American healthcare system outsources this burden to people can ill afford it? I bet the answer is yes. Will it undercut its own message by spelling it out like an op-ed, then cracking a dick joke? Unfortunately, I bet that answer is yes, too.

Sean T. Collins (@theseantcollins) writes about TV for Rolling Stone, Vulture, The New York Times, and anyplace that will have him, really. He and his family live on Long Island.

Read the full article here