“Rust,” as the whole world knows, is a movie that was the seat of a horrific on-set tragedy. During the shooting of a scene at the Bonanza Creek Ranch in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Alec Baldwin, who is the film’s star and one of its producers, discharged a gun that was being used as a prop and that somehow contained live rounds. (After all the recriminations and indictments and lawyers and trials and global media scrutiny, it has never been remotely determined how those rounds found their way onto the set or into the chamber of that gun.) The weapon went off, killing the film’s cinematographer, Halyna Hutchins, and injuring the director, Joel Souza.

Now that “Rust” has been completed and is finally being released (on May 2, simultaneously in theaters and on streaming), this terrible event regrettably but inevitably places “Rust” on that small but dicey roster of films that become famous because someone got violently killed in the process of making them. Is it part of the tainted karma of this category that the films themselves end up struggling to justify their existence? Vic Morrow was beheaded by a helicopter blade during the shooting of the John Landis episode of “Twilight Zone: The Movie” (1983), and that episode was easily the film’s worst. Brendan Lee was killed by a gunshot during the filming of “The Crow” (1994), and since his character, a rock ‘n’ roller who is murdered and resurrected, presided over the movie like a ghost, the slipshod slovenliness of “The Crow” only seemed to heighten the senselessness of Lee’s death.

“Rust” is a better movie than either of those. It’s a handsome and watchable indie art Western, set in 1882, that turns into a sentimental cross-generational buddy film. Yet I can’t say that the movie, in the end, is especially good. It’s got a bare-bones plot, it lopes along more than it takes wing, and for no good reason it’s two hours and 19 minutes long.

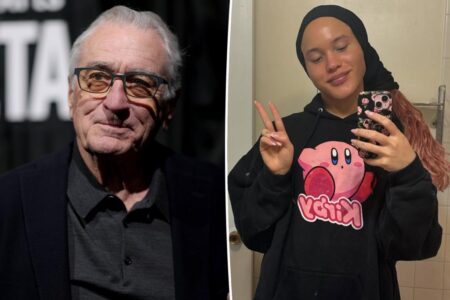

Baldwin, playing a grizzled criminal gunslinger who is also a caring grandpa, does his best to lend the film a menacing movie-star charisma. But as much as I’m a fan of Baldwin as an actor, he doesn’t fit smoothly into the period setting. Despite his repeated use of “ain’t,” he comes off as an anachronism — a contempo middle-class actor with a voice that seems too light and high (something I’ve never thought about him before), impersonating the sort of reticent man of few words that Kevin Costner can play in his sleep.

Baldwin’s overly cultivated badass sharpshooter, with his bushy gray beard, white Stetson, and saddlebag eyes, is named Rust — Harland Rust, to be exact. He shows up to rescue his grandson, 13-year-old Lucas Hollister (Patrick Scott McDermott), who in the first part of the film is living on a farm in Wyoming Territory with his younger brother, Jacob (Easton Malcolm). Both their parents are dead, and they’re trying to make a go of it, feeding the chickens and hogs, fending off an ominous wolf. But a hostile encounter in the town’s general store reveals Lucas to be a kid who will lash out when challenged. He breaks another kid’s arm, and when that kid’s varmint of a father shows up, demanding that Lucas pay his debt by going to work for him, Lucas takes matters into his own hands; he kills the father dead. He is soon arrested and sentenced to be hanged (which seems a jarringly extreme penalty for someone his age, even in the waning days of the Wild West). And that appears to be his fate until Rust, his mother’s father, enter the picture.

Patrick Scott McDermott, who plays Lucas, is a good young actor with a stoic rock-star pout. There are moments you look at him and think he could be a Chalamet in the making. But the role of Lucas is underwritten; the film simply accepts that this kid could be violent beyond his years without coloring in any unsettling emotional undercurrents. The whole movie, in fact, is underwritten. That’s the problem with it. (It’s why you feel the run time.)

Rust busts Lucas out of jail, and the two make their escape on horseback; they are now fugitives whose every move is being tracked. A posse is put together to hunt them down for a $1,000 reward, and a couple of these wild bunch of lawmen are colorful characters, starting with their leader, a Wyoming marshal named Wood Helm, played by Josh Hopkins with the stoic frontier magnetism of a ravaged Abe Lincoln. (He’s an early expert at forensics.) The Aussie actor Travis Fimmel has what you might think of as the Tom Hardy role — a bounty hunter named Fenton “Preacher” Lang who’s a Bible-spouting Christian and a charming sociopath, not necessarily in that order.

The trouble with “Rust” is that once Rust and Lucas get on the road south, heading for Mexican territory with the posse right behind them, the whole thing becomes a slow-poke chase movie, without much in the way of twists or revelations or, you know (sorry to use this outdated phrase), character development. Rust’s life story gets sketched in. He was originally from Chicago, he became a bank robber after the Civil War for reasons he wasn’t totally responsible for, and he turns out to be a ruthless SOB with a heart of gold. And while we’re supposed to be touched by the bond that develops between him and Lucas, it felt rote to me, less “Shane” than “True Grit Lite.”

Halyna Hutchins’ dusk-and-sunset cinematography, abetted by the work of Bianca Cline, may be the best thing about “Rust”; the film has a moody sensuality to it. But as written and directed by Josh Souza, the tale the film is telling comes down to Rust and Lucas stopping at one place and then another, never settling in long enough to have those places mean much; the posse will then show up at those same settings. “Rust,” in its picaresque way, is more vigorous than Costner’s “Horizon” films, yet it has an arid quality, enhanced by Lilie Bytheway-Hoy and James Jackson’s modernist musical score. The film finds a token place for Native characters, but it never summons the kind of spirit you saw in “Tombstone,” a movie that demonstrated how a retro Western could be serious without being joyless. Will the offscreen tragedy that now defines “Rust” make viewers curious to see it or turn people off? Either way, those who seek it out will find that the movie “delivers” without ever becoming an adventure to remember.

Read the full article here