Now that Christmas is around the corner, you’d think that the only music Mariah Carey ever created had tambourines jingling, trumpets blaring and sleigh bells ringing in the background.

This season marks the 30th anniversary of her legendary album, “Mariah Carey Merry Christmas.” Tickets to her Christmas tour are on sale and in high demand. According to Billboard, her iconic song, “All I Want for Christmas is You,” is one of the most popular songs in holiday music history.

I recently found myself careening down my own Mariah-shaped rabbit hole when I logged onto my Amazon account to shop for a pair of track pants only to discover the musician’s sparkling holiday collection. My hunt for activewear was soon forgotten, replaced by a burning need for a Mariah-inspired snow globe, or a gold ornament with the letter M stenciled on it in the kind of typeface that screams incomparable cultural icon. (Has Microsoft yet to name a font after the superstar? If not, they should. I propose something with the word “royal” in it.)

I mean, seriously. Who couldn’t use a Mariah Carey outdoor lawn inflatable Christmas decoration?

It’s natural, now, to equate the artist with all things Christmas. But the rest of her discography is also iconic, especially to those who spent the ’90s devouring, and re-devouring, her earliest records. Mariah Carey is so much more than her legendary Christmas album.

My own love affair with the mega-star’s music far predates what we’ve come to know as her holiday anthems. I was 12 years old when “Mariah Carey MTV Unplugged” topped the charts. My grandparents bought me the cassette tape during a random shopping trip to a mall when I visited them in Florida. By then, she had been a chart-topping recording artist with international fame for two years. I wasn’t at all familiar with her name or her music, but my grandparents had said that I could purchase a single item from the record store.

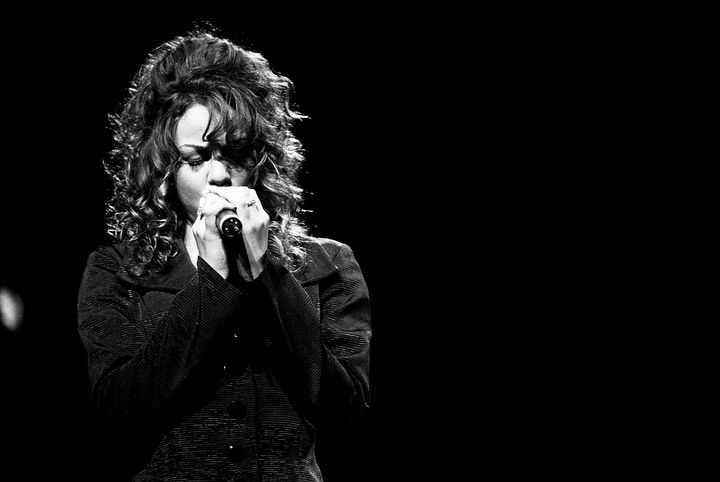

Kevin Mazur via Getty Images

My reasons for choosing Mariah’s tape had nothing to do with my nascent musical tastes. The fact is, I wasn’t used to seeing celebrities with wild curly hair. My own frizzy mop was one of the earliest signifiers of difference between my peers and me, and never in a good way. I admit it: I was drawn to her “Unplugged” album first and foremost because of how much space her hair seemed to take up on the cover. It made me feel just a bit more normal than I was used to feeling.

Later that day, I shoved the cassette into my Walkman and began hand-washing the dishes in my grandmother’s kitchen. Within several bars of the opening song — an acoustic version of “Emotions” — goosebumps ran up and down my arms. I knew in that moment that, like Mariah, I wanted to do something big with my voice. Within a year, I began auditioning for talent shows, community theater and taking voice lessons. I wasn’t bad, but I ultimately didn’t have the guts to professionally pursue music in the face of crushing competition and impossibility.

What I know now but didn’t know then was that I was a child longing for an artistic identity in the face of an ever-crumbling homelife. As I grew up, Mariah’s posters wall-papered my bedroom, and I listened to her music on my Walkman on my way to and from school. As a teenager, I wore a black leather jacket that resembled hers and even donned a similar heart-shaped charm on a gold chain like the kind she wore long before she began wearing butterfly-shaped jewelry. My hair got more and more out of control and, for the first time in my life, I actually didn’t mind.

Like a teenager with a crush on a famous actor, I lived, breathed and slept all things Mariah Carey. I could sing her songs in my sleep.

I know that I still occasionally sing her songs in my sleep. Even today, I’ll wake up with her more than 30-year-old lyrics on my lips.

In 1994, when Carey promoted her album “Music Box” at the now defunct New York City-based record store Coconuts, I stood in the pouring rain to wait for her signature. When I stood before her desk, me with a soaked “Music Box” poster and her on the other side flanked by security, she asked me for my name. For a solid 10 seconds, I trembled and could not remember. I’m pretty sure she gave me a look, as if to say, You have got to be kidding me.

Raymond Boyd via Getty Images

“Music Box” would go on to become one of the highest selling albums of all time, with legendary songs like “Dreamlover,” “Hero,” and her cover of 1960s Welsh band Badfinger “Without You” sealing its fate in the stratosphere of musical immortality. But while these are some of the record’s standouts, I’d always preferred her lesser-known songs. “Everything Fades Away,” which is the album’s bonus track but oddly absent from the album itself, remains one of my favorite Mariah Carey songs of all time.

Though I was a diehard fan, I couldn’t ever fully relate to the themes undergirding her earliest music, which often positioned men as the end all, be all of a woman’s existence. At that time, I was there for the incomparable vocals but less so for the lovesick lyrics. And then she released her sixth studio album, “Butterfly.”

I was soon to graduate from high school and bought the CD the weekend after it came out with money I earned babysitting. I knew instantly that this product was different from the sappy love songs and ballads Mariah was known for. Now she was singing about trauma. And I’m not talking about the trauma of a man who walks away — which I’m now convinced is probably the easiest to overcome on the scale of things that sometimes happen to people, and which she had already addressed in her music as early as the first album (“Vision of Love” and “Can’t Let Go” being two examples).

With “Butterfly,” Mariah began to let audiences in to what we’d later learn in her memoir, “The Meaning of Mariah,” was a pretty terrible childhood by any standard. “Close My Eyes” pulled back the veil on what we now know was an upbringing replete with emotional and physical neglect. It was the first time Mariah’s music had gone in such a raw and vulnerable direction.

With songs like “Close My Eyes” and “Outside,” “Butterfly” offered a new experience. This time, I felt her lyrics in my bones. With her deeper, harder to swallow music and storytelling about navigating childhood trauma and being born into a world she didn’t feel as though she fit into, I felt seen and understood for the first time. Her new music, for me, had become impactful in a way that her earliest ballads couldn’t quite achieve. As it happened, I came for the vocals and stayed for the trauma.

Admittedly, I’m less familiar with her latest music, and that’s a deliberate choice. I’m a bit protective of the discographies that defined my coming of age and am always a bit hesitant to watch musicians try to keep up with what the industry says they need to be. I’m now curious about the sort of explicit stories and experiences you won’t necessarily find in her songs, as with how she overcame her abusive marriage or how her own family used her, and perhaps worse, sold her out in her time of need (in her memoir, she described herself as “an ATM with hair” as her career began to take off). Mariah’s memoir has done well to satisfy my own curiosities about how she, too, came of age in a world that chews up women and unceremoniously spits them out. My only regret was reading it before bed; her stories actually gave me nightmares.

We Need Your Support

Support HuffPost

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

Out of all of her albums, I’ve listened to her holiday collections the least. I hope, as many of us participate in varying degrees of Mariah Carey idolatry this season, that fans turn to her earliest records to remind themselves of the vocals and range that catapulted her to the top of the industry. The perennial gift that her Christmas albums give those of us who came up with her is the reminder that she is so much more than campy holiday music.

Read the full article here